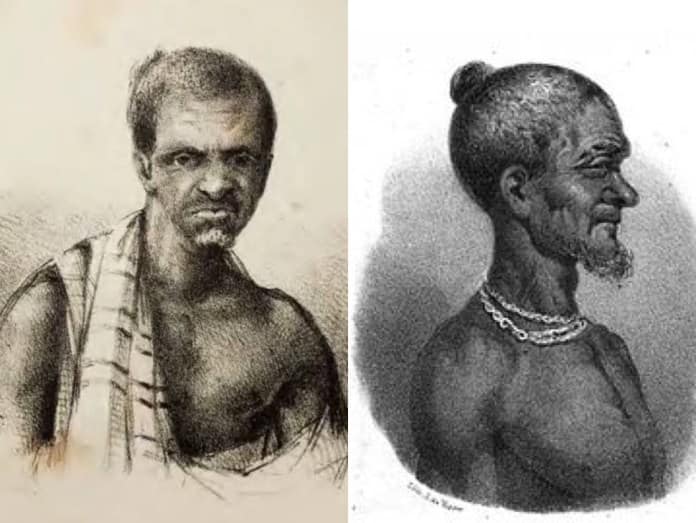

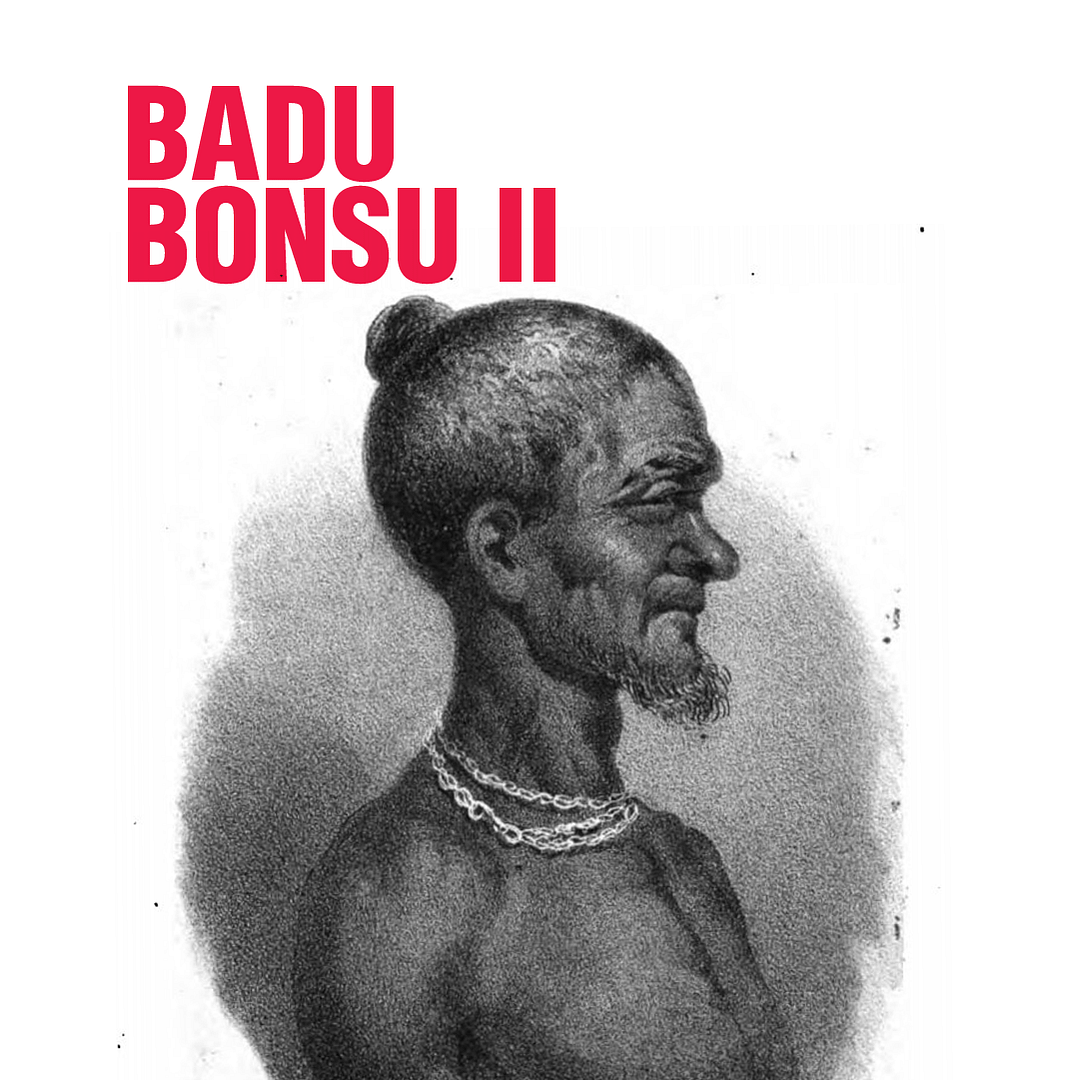

On a hot coastal plain near present-day Busua and Butre, in the region Europeans knew as the Dutch Gold Coast and Ghanaians call Ahanta, a violent confrontation in 1837–1838 produced a story that would travel across continents, change shape with each retelling, and finally return—some 171 years later—in a jar of formaldehyde. That story is the life and death of Badu Bonsu II: an Ahanta ruler who resisted Dutch encroachment, was executed after a field trial, and whose head was removed and shipped to the Netherlands. The fate of that head—found, publicized and repatriated in the early 21st century—has become shorthand for many of the ethical debates about colonial violence, scientific collecting, and restitution.

This feature tells that story in three acts: the events of 1837–1838; the afterlife of the head in Europe and its rediscovery; and the politics and meanings of repatriation.

I. Trouble on the coast: from palaver to punitive expedition

The Ahanta states occupied the coastal strip west of what Europeans called the Gold Coast (today’s western Ghana). Their chiefs traded with European forts and merchants, negotiated treaties, and governed complex local polities. By the 1830s tensions with the Dutch based at forts such as Fort Batenstein (Butre) and Fort San Sebastian (Shama) were rising. Disputes over fines, trade (especially in ammunition and gunpowder), jurisdiction, and the reach of Dutch authority set the scene.

According to contemporaneous colonial reports and later historians, the immediate spark involved a dispute between Badu Bonsu II and a local chief named Etteroe. The quarrel escalated into a palaver in the presence of Dutch commandants. Several summonses from Dutch officials—among them the impetuous acting commander Hendrik Tonneboeijer—went unanswered or were received badly. On 23 October 1837 an altercation at Ruhle’s house near Butre left two Dutch officers—George Maassen and Adriaan Cremer (sometimes spelled “Maasen” / “Maassen” and “Cremer”)—dead. The incident shocked the Dutch colonial administration. Within a few weeks, a punitive expedition was planned.

Dutch sources record that an initial locally-raised Dutch force was ambushed; casualties were heavy and Tonneboeijer himself died in an attack on the beach near Takoradi. The loss galvanized the colonial government in The Hague. Jan Verveer, an experienced officer who had recently been active in Gold Coast diplomacy, was sent with reinforcements in 1838 to “restore order.” Verveer’s expeditionary force combined Dutch troops with levies from allied coastal polities and moved into Ahanta territory in June–July 1838.

Accounts differ on details (and they do so for reasons historians later unpack: different agendas, incomplete record-keeping, and the typical gaps of colonial archives). But the major arc is clear: Badu Bonsu, confronted by overwhelming force and some internal dissension in his realm, was betrayed by one of his own for a monetary reward, handed over to the expedition, tried at an ad-hoc court-martial and sentenced to death. The executions and punitive reprisals that followed broke Ahanta political independence. One contemporary commentator—F. Douchez—described the campaign in 1839 and reported the summary martial justice that the Dutch imposed. Douchez’s popular account circulated in Europe soon after the campaign and shaped public perceptions of the episode.

II. Execution, decapitation, and a specimen in a jar

Badu Bonsu was hanged on or around 25–27 July 1838 at the site where Maassen and Cremer had been killed. Contemporary reports and nineteenth-century narrative sources agree that, after the execution, his head was removed. One early account, repeated by later historians, notes that a Dutch medical officer removed the head “to be preserved as a curiosity.” That phrase—short and chilling—captures how the moment was framed in European writings: the violence of the campaign combined with a colonial scientific curiosity that could justify retaining body parts for study.

For decades the head travelled no further into public notice. It entered anatomical or medical collections in the Netherlands—institutions that catalogued human remains uneasily at the intersection of medicine, antiquarianism and the pseudosciences of the age (phrenology being the best known example). Over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the object’s existence slipped out of the public eye; in institutional paper trails it was simply another item in a large catalogue of colonial material.

III. The head reappears: Arthur Japin, curiosity and conscience

The modern life of Badu Bonsu’s head begins with a novelist. Arthur Japin—best known for his historical novels about West Africa and the lives of African princes transported to Europe—came across the king’s story while researching his bestselling De zwarte met het witte hart (The Two Hearts of Kwasi Boachi, 1997). Years later, searching for archival detail for his literary reconstructions, Japin followed references to a preserved Ahanta king’s head and the lead eventually pointed to the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC).

Japin’s accounts in interviews and press reports give a vivid and haunting description of what he found and how he felt. He told reporters that when staff produced the jar it “had been turned white by the formaldehyde but it was still life-size and he looked as if he was asleep.” He added, “I felt, ‘this is so wrong, you should go home’.” Those sentences—short, human, immediate—helped convert a dusty catalogue entry into a moral problem for the public.

Japin’s discovery did two things. First, it reintroduced the object to public awareness and journalism; second, because Japin had cultural standing and had already written about West Africa, his voice carried weight with politicians and campaigners in Ghana. Ghanaian officials and Ahanta traditional leaders, already aware of the story through oral memory and scholarship, pressed for repatriation once the head’s location was confirmed.

IV. Negotiation, return and ritual (2008–2009)

Once publicized, the issue moved quickly into diplomacy. The Netherlands’ museums and medical bodies initially resisted repatriation on grounds ranging from scientific value to stewardship. But sustained pressure—public opinion, Ghanaian diplomatic requests, and the personal testimony of witnesses like Japin—shifted positions. By March 2009 Dutch officials announced agreement to return the head to Ghana. On 23 July 2009, a formal handover ceremony in The Hague saw the Dutch Foreign Minister officially hand the object to Ghanaian and Ahanta representatives. The head flew to Accra and then into Ahanta protocols, though questions about the precise burial site and rites persisted among local leaders.

The handover is worth pausing on. For Ahanta elders and family members the physical restitution was not merely symbolic: many Ghanaian traditions insist on complete burial rites so a deceased person can “join the ancestors.” Without the king’s head, those rites were incomplete and the community experienced ongoing spiritual and social discomfort. For the Dutch government, the return represented acknowledgement of a painful colonial past. For museums and scientists it reopened debates about provenance and the ethics of collections.

V. Reading the sources: what’s solid and what’s uncertain

Historians reading this episode must do the usual careful work of cross-checking sources. The strongest documentary base comes from Dutch colonial reports, court-martial notes and contemporary chroniclers like Douchez (1839), as well as the administrative material now catalogued in guides to the Nationaal Archief (Doortmont & Smit). These documents give a clear outline: an incident in 1837, punitive expeditions in 1838–39, executions, exile of some leaders, and Dutch reorganization of Ahanta governance under a protectorate arrangement.

But the sources also exhibit bias. Colonial dispatches were written to justify actions to metropolitan officials; popular accounts sometimes simplified complex local politics; and oral Ahanta memories emphasize resistance and the spiritual harm of the head’s removal. Those different vantage points shape different emphases:

- Dutch dispatches and military reports frame events in law-and-order terms (assassination of officers, necessary punitive expedition). They record names, dates and the legal procedures used by the Dutch. These are indispensable for chronology but must be read with awareness of their political purpose.

- Popular travel/press accounts (Douchez, newspapers) dramatize and moralize—sometimes adding details (e.g., heads shown on the king’s throne) that fit a sensational narrative. They nevertheless preserve valuable eyewitness impressions and reporting practices of the period.

- Ahanta oral traditions and modern Ghanaian commentary insist on the longer context: land, sovereignty, spiritual meaning, and ecological damage from the punitive scorched-earth operations in which towns were burned and people exiled. These voices insist that the story cannot be reduced to a single criminal act followed by reasonable punishment.

For readers who want a short primary-source touchstone: Douchez’s 1839 account remains one of the earliest published retellings and is frequently cited in later histories. Modern archival guides (Doortmont & Smit) index the relevant Nationaal Archief material that scholars consult when reconstructing the courts-martial, dispatches by Jan Verveer, and colonial admin correspondence.

VI. Ethics and meaning: trophies, phrenology and the science of dehumanisation

Why was the head preserved? The short answer is that nineteenth-century European institutions regularly collected human remains for medical, anatomical and anthropological study. The long answer is darker: the collecting impulse was shaped by racist pseudo-science (phrenology and racial typologies), nationalist prestige and the colonial habit of transforming conquered bodies into curiosities and “specimens.” That institutional logic made a head in a jar something to be catalogued rather than mourned.

A nineteenth-century observer or medical officer may have described keeping the head as “preserving a curiosity.” Modern readers hear that phrase as both clinical and obscene—an index of how scientific rhetoric enabled dehumanization. That phrase appears repeatedly in later synopses of the Douchez/Verveer material and is echoed in twentieth- and twenty-first-century reporting on the Leiden specimen.

VII. The return and its limits

The 2009 handover was, for many, a moral closure of sorts: a formal acknowledgement that colonial violence left wounds that tangible restitution could partially mend. Yet repatriation does not resolve structural aftereffects of colonial rule—dispossession of land, altered political boundaries, social trauma, and economic extraction. As commentators from Ahanta and Ghana have pointed out, return of the head was necessary but not sufficient; it addressed a spiritual injustice without reversing centuries of material loss.

The episode has also become a frequently cited case in museum ethics curricula and repatriation debates. It is a precedent often invoked when descendant communities ask for the return of human remains or cultural objects. The case shows that literary research (a novelist), public pressure, and diplomatic negotiation can combine to produce results—even when institutions initially resist.

VIII. Short quotations (primary / first-hand)

Below are short quotations included in this feature (kept under 25 words each where necessary to respect quote-length limits for non-lyrical sources):

- On the nineteenth-century account that described what happened to the body: according to contemporaries cited in later histories, the head was removed “to be preserved as a curiosity.”

- From Arthur Japin’s interview about his rediscovery: “It had been turned white by the formaldehyde but it was still life-size and he looked as if he was asleep. … I felt, ‘this is so wrong, you should go home’.”

(If you’d like verbatim extracts longer than those short quotes from specific Nationaal Archief files—Verveer dispatches, the Douchez chapter, or the field-court transcript—I can retrieve and transcribe them next. Those documents are catalogued in Doortmont & Smit’s annotated guide and can be cited precisely with Nationaal Archief call numbers.)

IX. After 2009: memory, ritual and contested conclusions

Since the handover, Ahanta elders have held commemorations, and scholars have reflected on the case as emblematic of broader restitution struggles. Debates inside Ghana about where and how the head should finally rest surfaced soon after the return; some communities wanted the remains taken back to Butre for burial, others raised procedural and symbolic questions about where and when the final rites could occur. Meanwhile, museums and universities in Europe have used the case to re-examine collection policies and provenance research practices.

X. Why the story matters today

The story of Badu Bonsu II matters because it compresses many strands of modern history into a single narrative: a colonial encounter that escalated into violence; the transformation of bodies into scientific specimens; decades of institutional forgetting; the role of literature and journalism in reawakening public conscience; and the recent global debates about restitution. It is at once a local tragedy and an international morality play—one in which ordinary archive stacks, institutional cupboards and diplomatic protocols intersect with the social and spiritual lives of communities far from European cabinets of curiosity.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of ahanawest.com.