The Long Silence

For more than a century, Ahanta’s story lay buried beneath European archives and dusty museum shelves. The Dutch, embarrassed by the grotesque legacy of colonial violence, kept the secret of Badu Bonsu II’s head hidden in their institutions. In Ghana, the Ahanta people mourned their vanished king without ever knowing what became of his remains. The story was passed from elder to elder, whispered in family compounds and told in twilight gatherings by the sea. Children were told that the King had not died — that he had journeyed “to the land of white men” and would one day return to reclaim his throne.

But history has a way of returning — sometimes through the most unexpected paths.

Discovery in a Jar

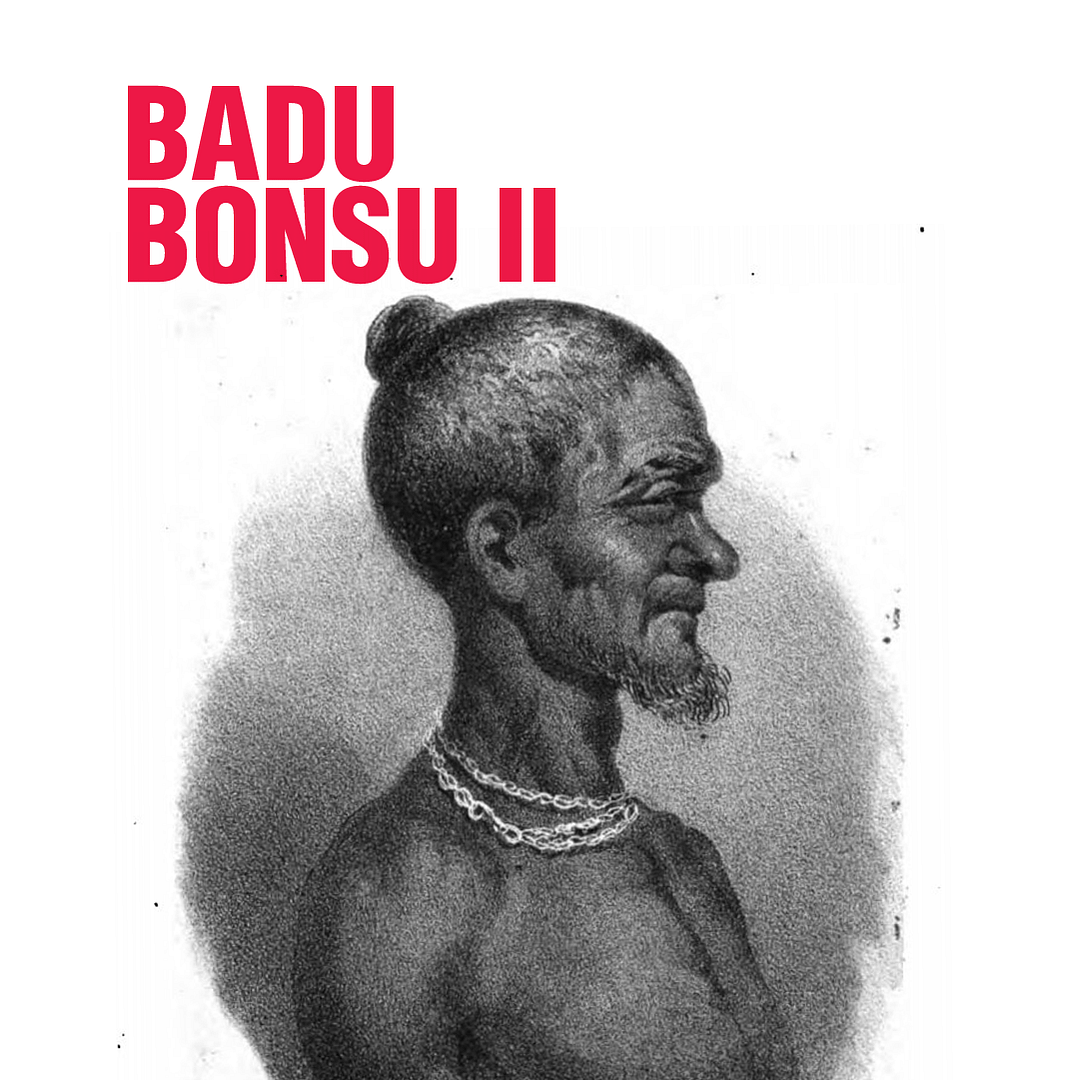

In 2002, Dutch novelist Arthur Japin, while researching for a novel on race and identity, stumbled upon a locked cabinet in the Leiden University Medical Center. Inside was a preserved human head — dark-skinned, eyes still discernible, the expression frozen in defiance. A small label beneath it read: “Badu Bonsu II – executed Gold Coast, 1838.”

Japin was shaken. “It looked as if he had been waiting,” he later wrote in The Two Hearts of Kwasi Boachi. “His face was not at peace — it was proud, it was questioning. I felt as if he was still demanding to know why.”

That preserved head was not just a relic — it was the face of a kingdom humiliated, a symbol of how Africa’s dignity had been literally bottled and displayed as science.

The head had been taken to the Netherlands by Dr. Frederick Riedel, a Dutch military doctor who, according to an 1839 report, had assisted in the King’s execution and personally transported the head “as a specimen of savage anatomy.” It was later handed to the University of Leiden for anthropological study during a time when European scholars obsessed over racial measurement and “scientific classification” of humans.

For 170 years, the King’s remains sat in that jar — unacknowledged, unburied, unatoned.

The Agitation for Justice

When news of Japin’s discovery broke in Ghana around 2009, it sent shockwaves across the country, particularly in Ahanta. Chiefs, historians, and activists demanded that the Dutch government return the head immediately. Traditional leaders like Nana Kobina Nketsia V, Omanhene of Essikado, and cultural advocates from Takoradi spoke passionately about the moral wound that remained open since the colonial era.

“This is not about bones or artifacts,” Nketsia said in an interview with The Ghanaian Times. “It is about the desecration of a soul, the humiliation of a people, and the arrogance of empire.”

At the diplomatic level, Ghana’s then-Minister of Chieftaincy and Culture, Zita Okaikoi, opened formal negotiations with the Dutch government. The Dutch initially resisted, citing “ethical and procedural reviews.” But under mounting moral pressure, they relented.

The Journey Home

On July 23, 2009, a solemn ceremony was held at The Hague. Representatives of the Ghanaian government, Ahanta traditional leaders, and the Dutch foreign ministry gathered at a private chamber inside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A sealed wooden box was brought in — inside lay the remains of King Badu Bonsu II.

The Dutch Foreign Minister, Maxime Verhagen, addressed the gathering with visible discomfort:

“What happened here cannot be justified. The head of your king was treated as an object, not as a human being. Today, we seek to make a small but meaningful correction to history.”

From the Ahanta delegation, Nana Prah Agyensaim VI responded:

“We come not for revenge, but for restoration. Our king returns home at last. His spirit will no longer wander.”

The ceremony was brief but heavy with emotion. As Ghanaian traditional drummers played a soft rhythm of homecoming, Arthur Japin himself stood at the back, silently weeping. “I felt relief,” he later told De Volkskrant. “It was as if he could finally go home to sleep.”

The Homecoming and Burial

When the King’s remains arrived in Ghana, thousands of Ahanta people gathered along the coastal roads between Takoradi and Busua. The air was filled with drums, chants, and libations. Men wore black and red cloths, women wailed in rhythmic lamentation.

At Busua, the ancestral seat of Ahanta royalty, a grand durbar was held. The coffin was draped in rich kente cloth, adorned with gold ornaments — a symbolic reversal of the dignity stolen by the Dutch. The priests of the kingdom poured libation to invoke the spirits of the ancestors.

“Welcome home, our King,” the elders intoned. “You went in chains, but you return as a conqueror.”

The burial took place near the royal palace, within sight of the ocean that had once carried slaves and soldiers. For the first time in 171 years, the cycle of desecration was broken.

Revisiting the Archives

In the wake of the repatriation, Dutch historians revisited their own records with new humility. The archives of the Dutch Colonial Office at The Hague revealed a chilling level of bureaucracy surrounding the King’s death.

A letter dated October 1838, written by Commander François Douchez to the Dutch Minister of Colonies, read:

“The Ahanta King, called Badu Bonsu, was this day hanged for murder and rebellion. His head was separated to prevent any local veneration.”

Another report by H.F. Tengbergen, who served in Elmina, lamented privately:

“The people were steadfast even as their chief died. I fear we have killed not a rebel, but a sovereign defending his land.”

Earlier writings from Willem Bosman, though from a much earlier era (1705), had described Ahanta as “a state of great order and discipline, whose people excel in trade and dignity.”

The contrast between Bosman’s admiration and Douchez’s arrogance tells the story of Europe’s moral decline under empire. What had begun as admiration turned into domination — curiosity became cruelty.

The Ahanta Spirit

Despite the centuries of disruption, the Ahanta people never lost their sense of identity. Their language, rituals, and hierarchy of chieftaincy survived even through the colonial and postcolonial periods. The Ahanta stool, though symbolically broken after Badu Bonsu’s execution, was restored in the 20th century. The sea-facing town of Busua, now a serene coastal resort, still carries whispers of its royal past.

Modern Ahanta descendants — from scholars to fishermen — speak of their kingdom with pride and longing. “We are the people who once ruled the coast before the white man came,” says Kojo Eshun, a historian from Takoradi. “The Dutch may have taken our gold, but not our glory.”

The return of Badu Bonsu’s head became more than an act of restitution. It became a spark for cultural revival — a reminder that the past, though buried, still breathes in memory.

The Reckoning of History

The Netherlands, to its credit, has begun confronting this dark legacy. The return of Badu Bonsu II’s head set a precedent that opened debates on colonial restitution, especially regarding human remains and sacred artifacts. Dutch scholars like Albert van Dantzig and Pieter Emmer later urged that museums “must cease to hold human trophies under the guise of science.”

As van Dantzig wrote in his 2013 posthumous essay:

“The Ahanta story shows how greed and ignorance transformed partners in trade into masters and subjects. The debt is not material — it is moral.”

Ghanaian historians have echoed the same sentiment. “Colonialism was not just the theft of land and labor,” argues Prof. Kwadwo Opoku-Agyemang of the University of Cape Coast. “It was the theft of narrative — and by reclaiming our story, we reclaim our power.”

The Golden Kingdom Reimagined

Today, Ahanta land still glistens with the richness that once made it a coveted “Golden Kingdom.” The cocoa fields of Agona Nkwanta, the oil fields off Sekondi, and the pristine beaches of Busua and Butre all speak of abundance. Yet, beneath that beauty lies a deeper historical truth — one of endurance and rediscovery.

New generations of Ahanta youth have begun tracing their lineage, restoring royal symbols, and documenting oral histories. Cultural festivals like Kundum now serve not only as celebrations of harvest but as commemorations of sovereignty and survival.

“The sea took away our king,” says Nana Kwesi Nkrumah, a local elder, “but it also brought him back. That means our ancestors have forgiven. Now it is our turn to rebuild.”

Legacy of a Head, Spirit of a Nation

In the end, the story of King Badu Bonsu II is not merely one of colonial atrocity. It is a mirror — reflecting how empires rise and fall, and how memory can outlast might. The Dutch may have silenced Ahanta’s king for a time, but they could not silence the moral force of his defiance.

As Arthur Japin reflected years later:

“When I looked into his eyes, I felt a question that still hung in the air — not ‘Why did you kill me?’ but ‘Will you tell my story?’”

Now, that story has been told.

The King has returned.

And the Golden Kingdom, though wounded, still shines.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of ahanawest.com.