Part I: The Rise and Fall of Ahanta

Long before the first Dutch ship glided across the Atlantic coast of West Africa, the land between the Pra and Ankobra Rivers shimmered in wealth and order. This was Ahanta, a coastal kingdom of the Akan-speaking people whose ancestors traced their migrations from the ancient Ghana and Bono empires. Around the year 1229, guided by a leader described as possessing “whimsical powers,” they settled between forest and sea, establishing small chiefdoms that would soon unite into one of the richest civilizations of precolonial Africa.

By the 14th century, Ahanta had emerged as a formidable coastal state — a land glinting with gold, ivory, salt, and sacred authority. Its capital, Owulosua (later known as Busua by the Dutch), became a royal enclave where the king, seldom seen except during great festivals, sat literally upon gold. European explorers later recorded that his robes “glittered with powdered gold” and that “his stool and regalia were fashioned of it.”

The people lived by the rhythm of the ocean and forest — trading salt and fish for cloth and beads from the interior. Their festivals were grand, their rituals deeply spiritual. For an entire month each year, Ahanta celebrated its grand festival, marked by nights of drumming and dance, and days of sacred silence to invite the ancestors’ blessings for harvest and peace. It was a kingdom bound by reverence — to the gods, to the sea, and to the whale, Bonso, whose name symbolized majesty and endurance.

A Kingdom of Gold and Order

European chroniclers who came to Ahanta left behind detailed, if biased, descriptions of what they saw. In 1705, Dutch explorer Willem Bosman wrote from the Gold Coast that “the king of Ahanta wears gold upon his body as the very earth wears dust.” Bosman’s account portrayed a society with organized governance, skilled artisans, and an economy built on gold dust and trade with neighboring states.

Ahanta’s rivers, Bosman observed, “glitter with gold along their banks,” and its markets bustled with “fine cloth, salt, and ornaments of great price.” The people were proud, disciplined, and fiercely loyal to their king. Justice in Ahanta was swift and sacred. As Bosman noted, “If the king condemns you, your head shall be brought to him as proof that his word has not fallen to the ground.”

Later Dutch writers such as François Douchez (1839) and H.F. Tengbergen (1839) would describe the same land as a “glittering belt of order and abundance along the Gulf of Guinea,” remarking on its disciplined leadership and “astonishing wealth for a nation without written law.” These European observers, though motivated by curiosity and conquest, inadvertently preserved the memory of a thriving state before the great fracture came.

When the Dutch Came Ashore

The first contact between the Ahanta and Europeans came around 1590, when the Dutch began trading along the coast. What began as an exchange of goods and friendship soon deepened into dependency and deceit. The Dutch built forts along the shoreline, promising protection and partnership. In reality, they were laying the foundations of control.

Ahanta, rich in gold and strategically placed between Shama and Axim, became a target of Dutch ambition. Treaties were signed — often under duress or through manipulation — granting the Dutch trading privileges. Over time, these agreements eroded Ahanta sovereignty. When the Dutch began demanding more land and political submission, tensions flared.

By the early 19th century, the Dutch had entrenched themselves as colonial overlords. Their obsession with controlling the “Golden Coast” brought them into direct conflict with Ahanta’s proud rulers — none more defiant than King Badu Bonsu II.

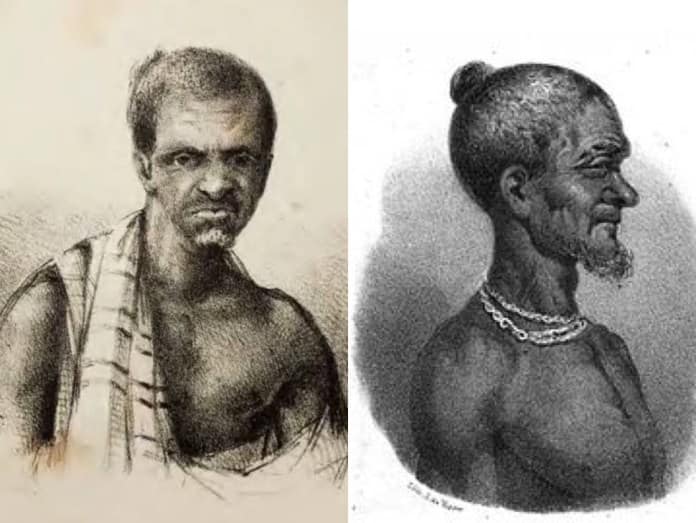

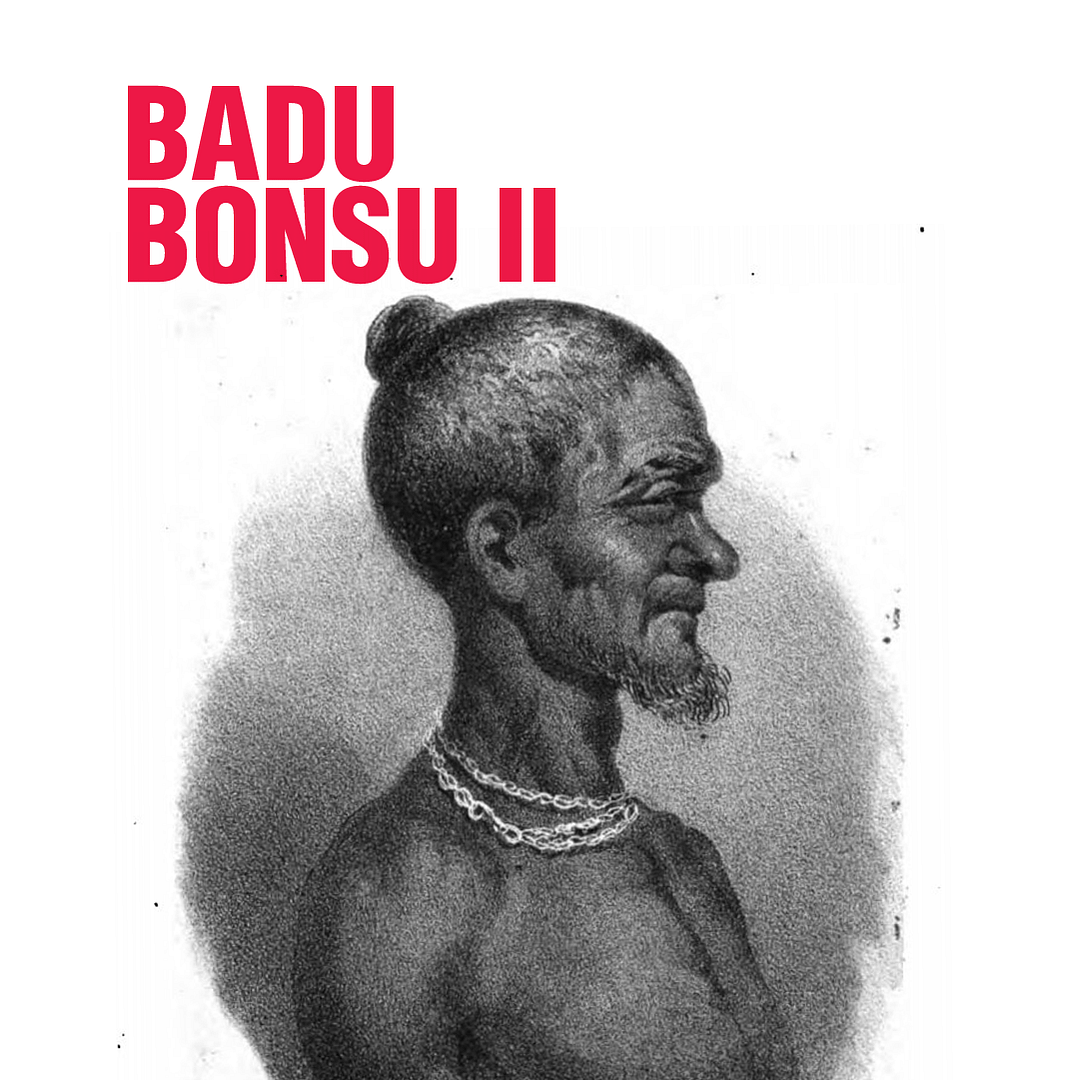

The Reign of King Badu Bonsu II

King Badu Bonsu II, ruler of the Ahanta Confederation, was described in Dutch reports as “a man of great courage and unpredictable will.” He reigned during a period of turmoil when the Dutch sought total dominance over Ahanta lands. Badu Bonsu II resisted — not merely for his throne but for the soul of his people.

Tengbergen’s 1839 report from the Dutch archives at The Hague describes him as “a formidable leader whose authority is absolute among his subjects, and whose distrust of the European is as deep as his love for Ahanta.” His defiance angered Dutch officers who demanded he acknowledge Dutch sovereignty. When he refused, the situation turned bloody.

According to colonial documents, the immediate cause of the Dutch–Ahanta War (1837) was the killing of two Dutch envoys sent to enforce Dutch policies. In one chilling Dutch account, the governor at Elmina wrote that the envoys’ heads were “displayed upon the king’s seat, a grotesque warning to those who come with deceit.” Oral Ahanta tradition, however, tells a different story — that the envoys had violated sacred custom and were punished for treachery, not diplomacy.

Whatever the truth, it became the pretext for a brutal Dutch invasion.

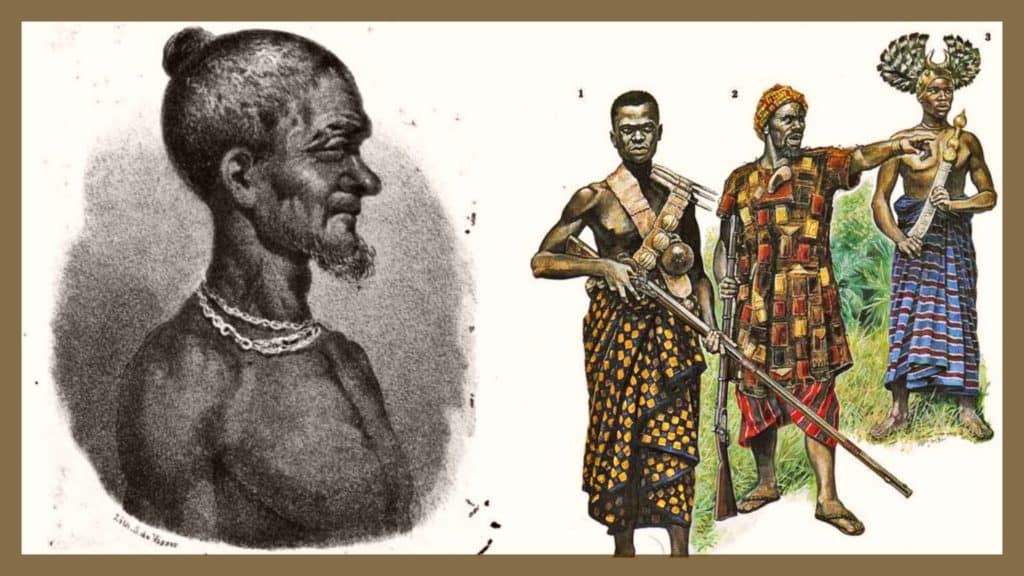

The Fall of Busua and the Beheading of a King

In July 1838, Dutch General Jan Verveer led a heavily armed expedition into Ahanta. The campaign, according to the official Dutch report, was meant to “restore order.” In reality, it was an extermination. Villages were razed, chiefs executed, and gold seized. The once-beautiful palace at Busua was stormed after fierce resistance. Inside, Dutch soldiers found chests of gold dust, regalia, and jewels — treasures accumulated through generations.

A Dutch officer recorded in his field notes:

“We entered the palace of the King of Ahanta and found the floor itself glimmering with gold. The air was thick with smoke and grief. The king was dead, his head taken, and his kingdom undone.”

King Badu Bonsu II was captured, tried by a military tribunal, and beheaded. His head was placed in a jar of formaldehyde and shipped to the Netherlands — a grotesque trophy of colonial conquest. For more than a century, it sat in the anatomical collection of Leiden University, misfiled among specimens, forgotten by all but history.

The Dutch looted not only gold and regalia but dignity itself. Ahanta’s royal towns — Busua, Apemenyim, Takoradi — were pillaged and burned. For ten years, the kingdom was left without a ruler. Dutch garrisons patrolled the ruins. The once-proud “Golden State” had been reduced to silence and servitude.

A People in Ruins

After the war, thousands of Ahanta were deported to the Dutch East Indies as slaves on sugar plantations. Those who remained were subjected to colonial rule. The Dutch divided Ahanta into administrative districts, replacing the royal hierarchy with colonial commissioners.

Albert van Dantzig, in his 2013 study The Dutch and the Guinea Coast 1674–1872, wrote,

“Ahanta, once a glittering jewel among the Akan polities, was left prostrate. Its people dispersed, its rulers decapitated, and its gold appropriated by those who claimed to bring civilization.”

The trauma ran deep. With the collapse of traditional leadership, social cohesion eroded. Rituals once sacred to the Ahanta gods were outlawed. The people who had once been feared and admired became subjects of pity and neglect.

By the late 19th century, as the British replaced the Dutch on the Gold Coast, Ahanta’s identity had faded into the margins of colonial maps. Its lands were absorbed into the Western Province of the Gold Coast Colony, its people scattered across plantations, fishing villages, and the expanding port town of Sekondi-Takoradi.

Once known as the “Golden Coast within the Gold Coast,” Ahanta had been stripped of both gold and glory.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of ahanawest.com.